In an era when smartphone cameras offer unprecedented convenience and digital technology allows for instant results and unlimited shots, something unexpected is happening in photography: film is making a dramatic comeback. Sales of film cameras—both new and vintage—have surged, film manufacturers are introducing new stocks rather than discontinuing them, and darkrooms are reopening in cities around the world.

This resurgence raises fascinating questions about our relationship with technology, creativity, and the photographic image. Why, in an age of technological advancement, are so many photographers choosing to work with a medium that is comparatively expensive, labor-intensive, and limited? What does this revival tell us about contemporary visual culture and artistic practice?

The Digital Disruption and Film's Decline

To understand film's renaissance, we must first acknowledge its near-extinction. At the turn of the millennium, film photography was the dominant medium for both professional and amateur photographers. Kodak, Fujifilm, Ilford, and other manufacturers produced hundreds of different film stocks, and photo labs could be found in nearly every neighborhood.

The arrival of consumer digital cameras in the late 1990s, followed by the camera phone in the early 2000s, changed everything. By 2010, digital had almost completely replaced film in professional contexts, from photojournalism to wedding photography. Kodak, once an industrial giant, filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Photo labs closed by the thousands, and countless darkrooms were dismantled or converted to other uses.

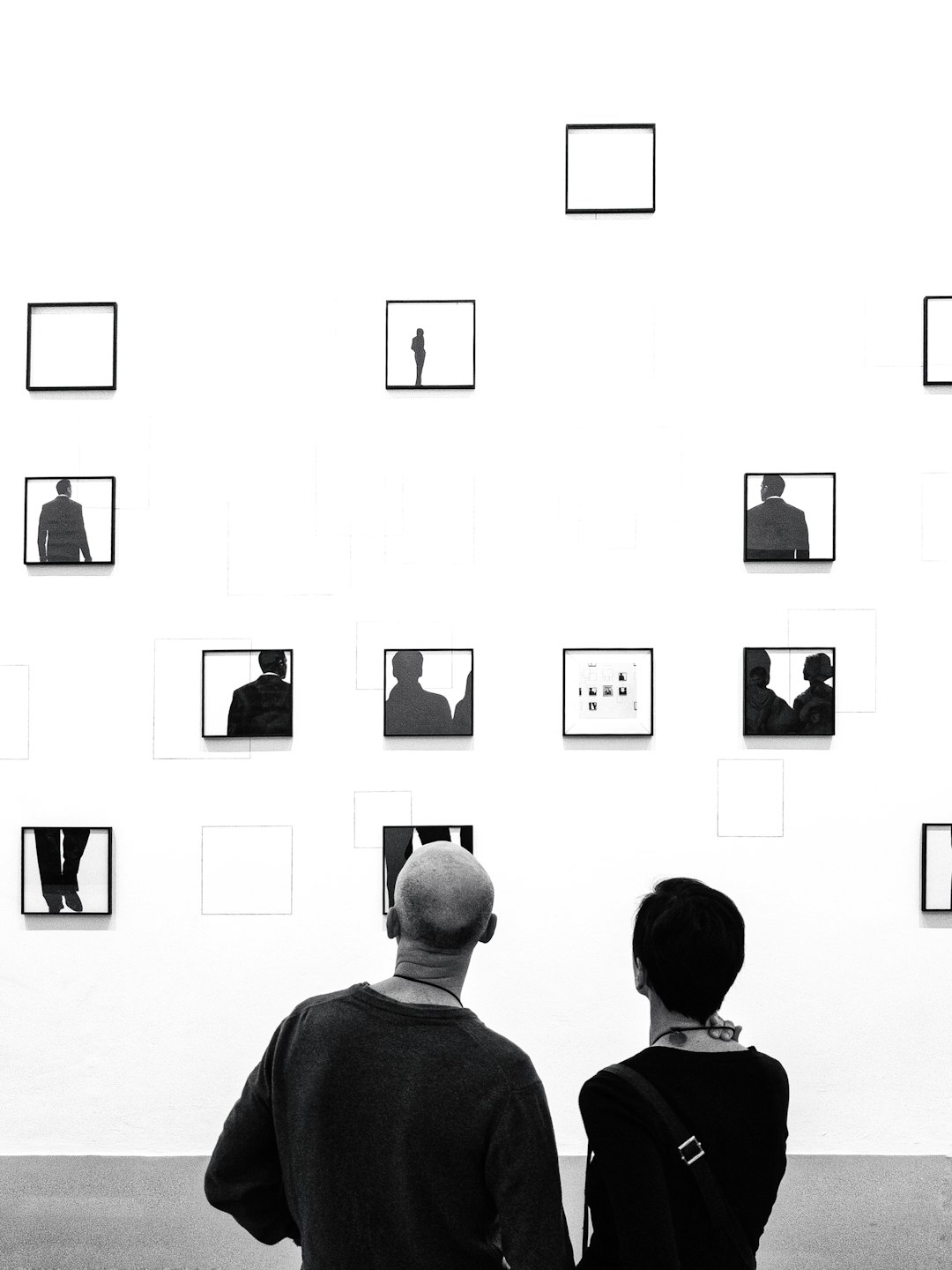

Vintage film cameras have become highly sought-after by a new generation of photographers

This shift seemed irreversible—the natural progression of technology rendering an older medium obsolete. Digital offered undeniable advantages: immediate results, zero processing costs, and the ability to shoot thousands of images without changing media. The convenience was revolutionary, democratizing photography in unprecedented ways.

Yet something was lost in this transition. The physicality of film—its grain, color rendition, and dynamic response—created a distinctive look that many digital systems initially struggled to replicate. The discipline imposed by limited exposures fostered a more thoughtful approach to image-making. And the darkroom process offered a tactile, alchemical experience that clicking through Lightroom presets couldn't match.

The Unexpected Revival

Around 2015, something surprising began to happen. While digital photography continued to dominate the mainstream, a growing number of photographers—many too young to have grown up with film—began seeking out analog processes. What started as a niche interest has grown into a significant movement that has surprised industry observers and manufacturers alike.

The numbers tell a compelling story. Fujifilm reported a 35% increase in film sales between 2015-2019. Kodak Alaris, which took over Kodak's film business, has reintroduced previously discontinued stocks like Ektachrome E100. New companies like Lomography and FILM Ferrania have entered the market, while established manufacturers like Ilford report steady growth.

"We're seeing double-digit growth year over year in film sales, with particularly strong interest from photographers under 35. It's not just nostalgia—it's a new generation discovering film for the first time."

— Steven Overman, former Chief Marketing Officer at Kodak

Perhaps most tellingly, prices for vintage film cameras have skyrocketed. Models like the Contax T2, a premium 35mm point-and-shoot that sold for around $200 used in 2010, now regularly command $1,500 or more. Even basic mechanical SLRs and rangefinders that could once be found in thrift stores for pocket change have become coveted items.

But what's driving this revival? The answer is multifaceted, involving aesthetic preferences, creative processes, and cultural reactions to digital ubiquity.

The Aesthetic Appeal of Film

The distinctive look of Kodak Portra 400 film has made it a favorite among portrait photographers

One of the most obvious explanations for film's revival is its distinctive visual quality. Each film stock has unique characteristics—Kodak Portra's warm tones and forgiving highlights, Fuji Velvia's saturated colors, Ilford HP5's gritty contrast—that create looks that many photographers find compelling.

"Film has a soul that digital often lacks," explains portrait photographer Elena Jasic, who switched from digital to medium format film in 2018. "The way film renders skin tones and transitions between highlights and shadows creates a three-dimensional quality that I struggled to achieve digitally, even with the most expensive gear."

Film's grain structure differs fundamentally from digital noise, creating a textural quality that many find more organic and pleasing. Its non-linear response to light—the way it gradually rolls off highlights rather than abruptly clipping them—gives it a dynamic range that can be more forgiving in challenging lighting conditions.

"There's an inherent imperfection to film that feels more human," notes street photographer Marcus Lee. "The slight unpredictability of how a particular scene will render, the subtle color shifts in different lighting—these 'flaws' actually give the images character that perfect digital capture sometimes lacks."

Interestingly, as digital technology has advanced, many manufacturers have worked to incorporate film-like qualities into their sensors and processing algorithms. Features like "film simulation modes" on Fujifilm's digital cameras explicitly attempt to recreate the look of specific film stocks. Numerous software presets and filters offer "film looks" for digital images. These digital approximations have paradoxically heightened interest in the authentic analog experience.

Process and Intention

Beyond aesthetics, many photographers are drawn to film for the experience of working with it. The constraints and rituals of analog photography foster a different relationship with image-making that many find creatively liberating despite—or perhaps because of—its limitations.

"When I shoot digital, I often find myself taking dozens of variations of the same shot, then spending hours at the computer sorting through nearly identical images," says landscape photographer Thomas Rivera. "With film, I have 36 exposures per roll. That scarcity makes me more deliberate. I slow down, think more carefully about composition, and wait for exactly the right moment."

"The limitations of film don't restrict creativity—they enhance it. Working within constraints forces you to be more thoughtful, more precise, and ultimately more intentional with your vision."

— Carolyn Marks, Photography Instructor at Pratt Institute

The delayed gratification inherent in film photography also changes the creative experience. Unlike digital photography's immediate feedback, film requires photographers to wait—sometimes days or weeks—to see their results. This separation between capture and review creates a different psychological relationship with the images.

"There's a magic to opening a freshly developed roll of film," explains documentary photographer James Chen. "You've carried these latent images with you, sometimes forgetting what you've captured. That moment of discovery is something digital can never replicate."

For many film photographers, the physical process extends beyond capturing images to developing and printing. Darkroom work offers a hands-on engagement with the medium that transforms photography from a purely visual pursuit to a craft involving chemistry, precision, and tactile skills.

The darkroom process offers a tactile, alchemical experience that many photographers find deeply satisfying

"In the darkroom, I'm not just looking at my photographs—I'm making them with my hands," says fine art photographer Sofia Reyes. "Each print is unique, with subtle variations that come from the physical process. That handmade quality has become central to my artistic practice."

Cultural Context: Reaction and Resistance

Film's revival exists within a broader cultural context that helps explain its appeal. As digital technology has become ubiquitous in nearly every aspect of life, various analog media and processes have experienced similar resurgences—vinyl records, mechanical watches, handmade crafts, and even paper books have all defied predictions of their demise.

This phenomenon reflects a complex relationship with technology rather than simple nostalgia. For many, analog processes provide a meaningful counterbalance to digital saturation, offering experiences that are tactile, finite, and immune to the distractions of connected devices.

"There's something profoundly satisfying about using a machine that does exactly one thing and does it well," notes cultural critic Elena Matthews. "A film camera isn't going to interrupt you with notifications or tempt you to check social media. It creates a different quality of attention that many people find increasingly valuable."

The physicality of film also addresses growing concerns about digital impermanence. As cloud services change their terms, platforms shut down, and file formats become obsolete, the longevity of digital archives seems increasingly uncertain. Film negatives and prints, by contrast, exist as physical objects that can be stored, displayed, and passed down without requiring specific technologies to access them.

"I worry about what happens to all our digital photos in 50 years," says photographer and archivist Miguel Sanchez. "Will those cloud services still exist? Will the files still be readable? With my film negatives, I know that as long as the physical material survives, the images remain accessible without requiring any specific technology to view them."

For younger photographers who have grown up in an entirely digital environment, film offers something else: a connection to photographic tradition and history. The process of loading a camera, manually setting exposure, and developing film creates a tangible link to generations of photographers who worked with these same materials and constraints.

"When my students work with film for the first time, they're connecting with the fundamental principles of photography in a way that's often missed when starting with digital. They're not just taking pictures—they're participating in a tradition."

— Dr. Rebecca Wong, Professor of Photography, School of Visual Arts

The Hybrid Approach

While some photographers work exclusively with film, many have adopted a hybrid approach that combines analog capture with digital workflow. This pragmatic middle ground preserves what many consider the most valuable aspects of film—its aesthetic qualities and the shooting experience—while leveraging digital tools for convenience in editing, sharing, and archiving.

A typical hybrid workflow involves shooting on film, developing the negatives traditionally, then digitizing them with a scanner or digital camera. Once digitized, the images can be edited in software like Lightroom or Photoshop, then shared online or printed digitally.

"I love shooting medium format film for the quality and experience," explains fashion photographer Liam Parker. "But I don't maintain a darkroom. I develop my film at home, scan it, and then work with the digital files. This gives me the look I want without sacrificing the workflow efficiency my clients expect."

This hybrid approach has fueled much of film's commercial revival, making it accessible to photographers who appreciate film's qualities but work in contexts that demand digital delivery. It has also created a market for high-quality film scanners and digitization services that bridge the analog-digital divide.

Many contemporary film photographers use a hybrid workflow, scanning their negatives for digital editing and sharing

Manufacturers have responded to this hybrid approach. Kodak's recent introduction of "scan-optimized" film stocks designed to digitize well reflects the reality that many film photographs will ultimately exist as digital files. Similarly, Fujifilm has created new instant films for their Instax cameras that embrace the analog-digital intersection, including features like QR codes that link physical prints to digital content.

Challenges and Sustainability

Despite its renaissance, film photography faces significant challenges. The infrastructure that once supported it—from manufacturing facilities to processing labs—has been dramatically reduced. Many of the skilled technicians who maintained complex coating machines or formulated emulsions have retired. And the environmental impact of film chemistry remains a concern in an increasingly eco-conscious world.

Cost presents another barrier. Film photography requires ongoing material investment—each exposure has a tangible cost in film, processing, and potentially printing. As Jason Kim, owner of an independent photo lab, explains: "A serious amateur shooting five rolls a week could easily spend $5,000 annually on film and processing. That's a significant commitment compared to the essentially zero marginal cost of digital exposures."

Film's future sustainability depends on addressing these challenges. Some promising developments include:

- New Business Models: Subscription services like Film Supply Club offer regular deliveries of film at discounted prices, while lab cooperatives in cities like Berlin and Melbourne provide affordable processing through shared equipment and knowledge.

- Educational Initiatives: Organizations like the Analog Photography Association offer workshops and mentorship programs to preserve darkroom skills and chemistry knowledge.

- Environmental Innovation: Companies like Kodak are developing more eco-friendly processing chemistry, while community darkrooms increasingly implement chemical recycling systems.

- Digital Integration: Apps like FilmLab and Negative Lab Pro streamline the digitization process, making it easier for photographers to bridge analog and digital workflows.

Perhaps most importantly, film's future depends on maintaining a critical mass of users to support manufacturing at scale. "Film production has high fixed costs and requires significant volume to be economically viable," explains industry analyst Maria Chen. "If the community can sustain current growth rates for another few years, we'll reach a stable equilibrium that could sustain film photography indefinitely."

The Future of Film in Contemporary Photography

As we look ahead, film photography appears poised to maintain its position as a vital niche within the broader photographic landscape. Rather than competing directly with digital, film has found its place as a distinctive medium with unique characteristics and creative processes that appeal to certain photographers for specific applications.

In fine art photography, film continues to gain recognition for its distinctive aesthetic qualities. Major museums and galleries increasingly feature work shot on film, particularly in large format, where its resolution and tonal qualities remain competitive with even the most advanced digital systems.

In commercial contexts, film has established itself as a stylistic choice rather than a technical necessity. Fashion photographers like Jamie Hawkesworth and Harley Weir have built successful careers shooting predominantly on film, their distinctive look becoming part of their creative signature.

"The question isn't whether film or digital is better—they're simply different tools with different qualities. The exciting development is that photographers now have more options, not fewer, allowing for more diverse and distinctive visual expressions."

— David Burnett, Photojournalist

In education, many photography programs have reintroduced film and darkroom work into their curricula, recognizing that the technical discipline and fundamental understanding of photographic principles it develops serve students well regardless of the medium they ultimately choose.

Perhaps most significantly, film has found particular resonance with younger photographers who have grown up in an entirely digital world. For this generation, film isn't a nostalgic return to the past but a discovery of an alternative approach to image-making that offers distinctive qualities and experiences.

"My students didn't grow up with film, so they have no preconceptions about it being outdated or difficult," notes photography instructor Eliza Montgomery. "They approach it with curiosity and enthusiasm, discovering its qualities without the baggage of comparing it to how things used to be done."

Conclusion

The renaissance of film photography represents more than a nostalgic trend or resistance to technological progress. It reflects a maturing relationship with photographic technology, where the medium is chosen for its specific qualities rather than simply its convenience or novelty.

As digital photography has become ubiquitous, standardizing certain aspects of image-making and viewing, film offers an alternative that embraces physicality, chance, and craft. Its constraints foster intentionality, while its tactile nature satisfies a craving for tangible experience in an increasingly virtual world.

Community darkrooms and workshops have helped sustain film photography by creating spaces for learning and collaboration

For the foreseeable future, film appears set to continue its parallel existence alongside digital photography. Neither replacing nor being replaced by its electronic counterpart, film instead offers a complementary approach that enriches the photographic landscape through its distinctive aesthetic, process, and philosophy.

This persistence of analog methods in a digital age speaks to something fundamental about human creativity and expression. In photography, as in other art forms, the means of creation shapes the end result in ways both subtle and profound. By preserving and revitalizing film photography, the current generation of analog enthusiasts ensures that these unique creative pathways remain open for future exploration.

As photographer and educator David Alan Harvey once noted: "Don't shoot what it looks like. Shoot what it feels like." For a growing number of photographers, film continues to offer a uniquely compelling way to translate feeling into image—a translation that occurs not just in the final photograph, but in the entire process of creating it.