On a bright spring morning, I make my way through the industrial district of East London to visit the studio of Sarah Chen, one of the most innovative sculptors working in sustainable materials today. Her recent exhibition "Ephemeral Forms" at the Tate Modern received critical acclaim for its groundbreaking approach to biodegradable sculptures that engage with ecological themes while maintaining formidable artistic presence.

Chen's studio occupies the top floor of a converted factory building, where massive windows flood the space with natural light. As I enter, I'm greeted by the artist herself, dressed in well-worn work clothes, her hands stained with natural pigments from the morning's work.

From Finance to Fine Art

Unlike many contemporary artists, Chen didn't follow a traditional path through art school. After graduating from the London School of Economics and spending five years in investment banking, she made a dramatic career change at age 28, leaving the financial world to pursue her artistic calling.

"I always created things as a child," Chen explains as she prepares tea in the small kitchenette tucked into a corner of her vast studio. "My parents encouraged academic achievement above all else, so art became something private, almost secretive. But after years in finance, I realized I was living someone else's definition of success."

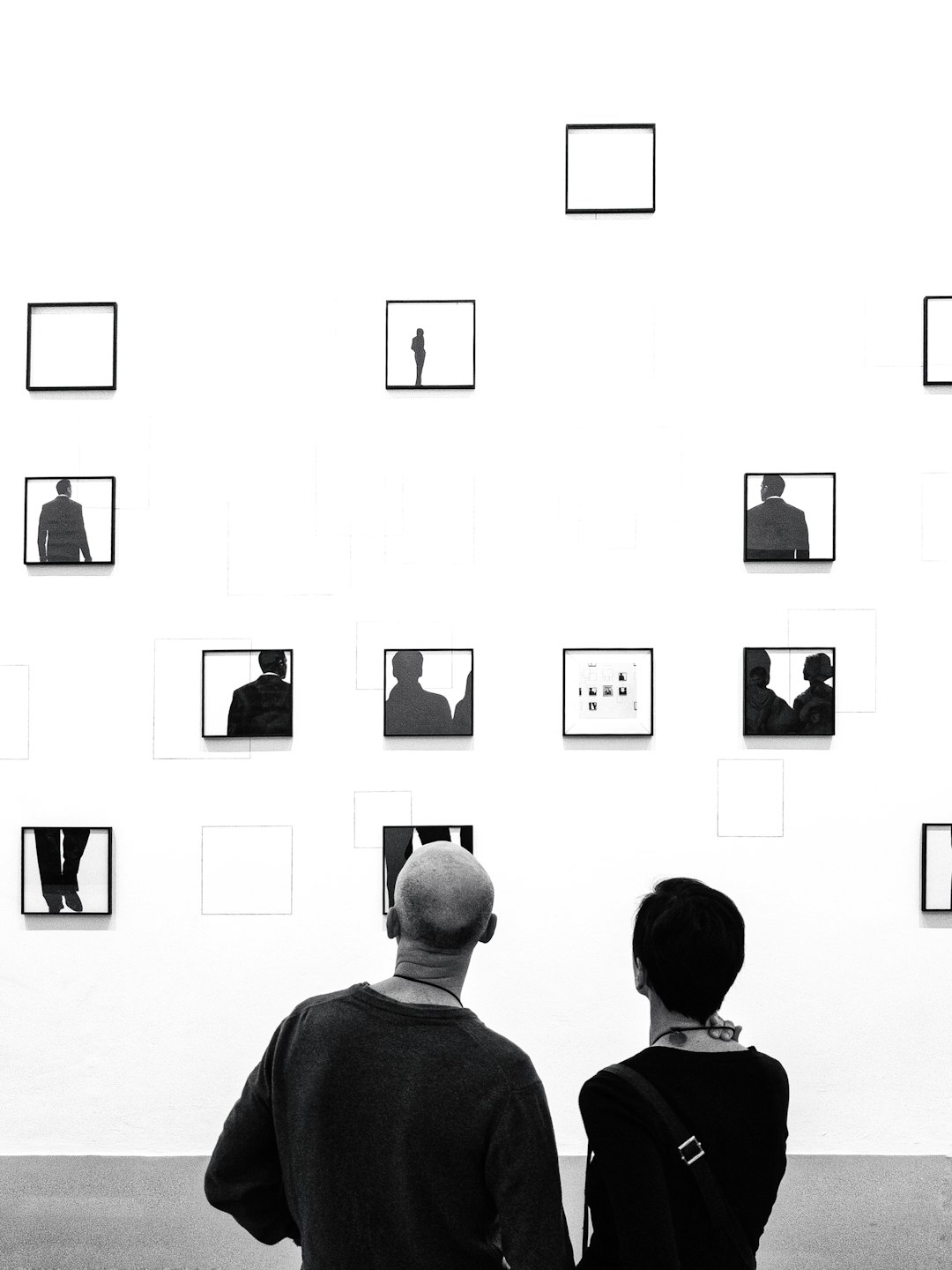

An early work from Chen's "Transitions" series, created during her first year as a full-time artist

Chen's decision to leave a lucrative career wasn't made lightly. She spent two years taking evening classes at Central Saint Martins while still working full-time, gradually building the skills and portfolio that would eventually allow her to make the leap.

"Those were exhausting years," she recalls with a smile. "I'd work in the City until 7 pm, then rush to class until 10 pm, then go home and practice until 2 am. But that period taught me discipline and commitment. When you're paying for your art education with a job you're trying to escape, you don't waste a minute."

Finding Her Material

As we walk through the studio, Chen points out various works in progress. What immediately strikes me is the diversity of materials: beeswax, mycelium (fungal root structures), alginate, compressed sawdust, and clay that she harvests and processes herself from a specific riverbank outside London.

"I was frustrated with the environmental impact of traditional sculpture materials," Chen explains. "Bronze casting is energy-intensive, resins are petroleum-based, and even stone quarrying has significant ecological consequences. I wanted to create work that spoke about our relationship with nature without contributing to environmental degradation."

"My materials aren't just mediums for expression—they're collaborators with their own properties, behaviors, and timelines. I don't impose my will on them so much as negotiate with them."

— Sarah Chen

This commitment to sustainable materials presented significant technical challenges. Chen spent nearly three years researching, experimenting, and developing techniques that would allow her to create durable works from biodegradable materials.

"Each material has its own personality," she says, handing me a small sculptural element made from mycelium. It's surprisingly light yet structurally strong, with a subtle organic texture. "Mycelium, for instance, grows rather than being shaped. You create conditions for it, suggest a form, but ultimately it follows its own logic. That surrender of control has transformed my entire approach to making."

The Working Process

Chen's current workspace showing various material experiments and works in progress

Chen's daily routine is structured yet flexible. She typically arrives at the studio by 8 am, beginning with what she calls "morning studies"—small experimental pieces that allow her to test ideas without the pressure of creating finished work.

"I don't believe in waiting for inspiration," she says firmly. "Creation is a practice, like meditation or exercise. You show up every day, and some days are more productive than others, but the consistency is what matters."

For larger pieces, Chen works methodically, beginning with sketches and maquettes (small preliminary models) before scaling up. Her current project, a commission for the atrium of a new sustainable architecture center in Manchester, involves a suspended installation of interconnected mycelium forms that will continue to evolve subtly throughout the exhibition period.

"This piece explores symbiotic relationships in natural systems," Chen explains, showing me detailed drawings of the planned installation. "The forms reference mycorrhizal networks—the 'wood wide web' through which trees communicate and share resources. I'm fascinated by these invisible connections that sustain ecosystems."

The technical challenges are considerable. Chen has developed a custom growing environment for the mycelium components, carefully controlling temperature, humidity, and air flow to achieve the desired structural properties. She works with biologists and material scientists to ensure her creations are both aesthetically compelling and structurally sound.

Influences and Inspirations

When asked about her artistic influences, Chen mentions traditional Chinese landscape painting, which she studied extensively during childhood visits to family in Taiwan. "The philosophy behind those paintings—the idea of capturing the essence rather than the appearance of nature—deeply informs my work," she explains.

Contemporary influences include Eva Hesse, whose exploration of organic forms and unconventional materials opened new possibilities for sculpture, and Andy Goldsworthy, whose ephemeral environmental works challenge traditional notions of permanence in art.

"I'm also deeply influenced by scientists," Chen adds. "Reading Merlin Sheldrake's work on fungi or Robin Wall Kimmerer's botanical writings often sparks more ideas than visiting galleries. The patterns and processes of the natural world are my primary inspiration."

"I'm not interested in mimicking nature—I'm interested in participating in it. My sculptures aren't representations of natural processes; they're instances of those processes."

— Sarah Chen

This perspective places Chen's work within a growing movement of artists engaging directly with ecological systems and environmental concerns, though she resists being categorized solely as an "eco-artist."

"Labels can become limiting," she says. "Yes, environmental concerns drive my material choices and inform my themes, but I'm equally concerned with formal qualities—with creating work that's visually and emotionally compelling regardless of its conceptual framework."

Challenges and Breakthroughs

Chen with her Turner Prize-nominated installation "Mycorrhizal Networks" (2023)

Chen's path hasn't been without obstacles. Working with living and biodegradable materials presents unique challenges for exhibition, collection, and conservation.

"When I first started showing these works, galleries didn't know what to do with them," she laughs. "Traditional conservation approaches are designed to preserve objects in their original state indefinitely, but my pieces are designed to change, evolve, and eventually return to the earth."

This ephemeral quality initially made selling work difficult, but Chen has developed innovative approaches to documentation and ownership. Some collectors purchase both the physical work and extensive documentation of its creation and evolution. Others commission new iterations of concepts rather than collecting the original objects.

"I've had to rethink what it means to collect and preserve art," Chen reflects. "In some ways, my work is closer to performance than traditional sculpture—it exists most fully in its unfolding over time rather than as a static object."

A significant breakthrough came in 2023 when the Victoria and Albert Museum acquired one of Chen's mycelium pieces along with her full documentation process, recognizing the importance of both the physical artwork and the knowledge embodied in its creation. This institutional validation helped establish a framework for collecting ephemeral works that has benefited many artists working with similar approaches.

Current Projects and Future Directions

Beyond her Manchester commission, Chen is preparing for a residency at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, where she'll collaborate with botanists on a series exploring endangered plant species.

"I'm particularly interested in plants that have developed unique adaptations to survive in challenging environments," she explains. "Their resilience and ingenuity offer powerful metaphors for human adaptability in the face of climate change."

Chen is also exploring more participatory approaches, developing workshops that invite the public to engage directly with sustainable materials and ecological concepts.

"Art has a unique capacity to make abstract issues tangible and emotional," she says. "Climate data might not move people to action, but a direct sensory experience of working with living materials can create new relationships with the natural world."

Looking further ahead, Chen hopes to scale up her work for public spaces, creating large-scale installations that transform environments and create immersive experiences.

"I'm interested in work that doesn't just occupy space but creates new ecosystems—both literally, in terms of incorporating living elements, and metaphorically, in terms of generating new relationships between people and places."

Advice for Emerging Artists

As our conversation winds down, I ask Chen what advice she would offer to young artists interested in working with sustainable materials.

"First, develop a deep understanding of your materials," she says without hesitation. "Not just technically, but ecologically and culturally. Know where they come from, how they're harvested or produced, what their lifecycle is."

She also emphasizes the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration. "Artists working with biological materials need scientific knowledge. Don't be afraid to reach out to experts in other fields—most scientists are delighted when artists take an interest in their work, and those collaborations can lead to extraordinary innovations."

"Be patient with yourself and with your materials. The most interesting discoveries often come from failure—from what happens when things don't go as planned."

— Sarah Chen

Finally, Chen stresses the importance of documentation. "When you work with ephemeral materials, documentation becomes an integral part of the work, not an afterthought. Develop a consistent system for recording your process from the beginning."

Reflection

As I prepare to leave, Chen shows me one last piece—a small, seemingly simple form made from beeswax and embedded with seeds. Over time, the beeswax will degrade, allowing the seeds to germinate and transform the sculpture into a living plant.

"This piece will never be exhibited," she tells me. "It's a personal reminder of why I make art—to explore transformation, regeneration, and the beautiful impermanence of all things."

Walking out of Chen's studio into the busy London streets, I'm struck by the contrast between the industrial urban environment and the living, breathing ecosystem she's created within it. Her work challenges us to reconsider not just our relationship with art, but our relationship with the material world and the ecological systems that sustain us.

In a cultural moment often dominated by digital experiences and virtual realities, Sarah Chen's deeply physical, temporal, and ecological practice offers a compelling alternative—one that embraces materiality, celebrates impermanence, and suggests new possibilities for art in the Anthropocene.